Previous research suggested that only a few rivers carry most of the plastic into the sea; new research suggests this is not the case.

Previous studies suggested that most plastics come from only some of the world's rivers: one study estimated that the top ten rivers were responsible for 50% to 60%; another for more than 90%.

The latest research, just published in Science Advances, updates our understanding of how these plastics are distributed. Lourens Meijer et al. (2021) developed higher resolution models of global river plastics. They found that rivers released about 1 million tons of plastics into the oceans in 2015 (with an uncertainty ranging from 0.8 to 2.7 million tons). About a third of the 100,000 river outlets they modeled contributed to this. The other two-thirds released almost no plastic into the ocean. It is an important point because we might think that most, if not all, rivers are contributing to the problem. This is not the case.

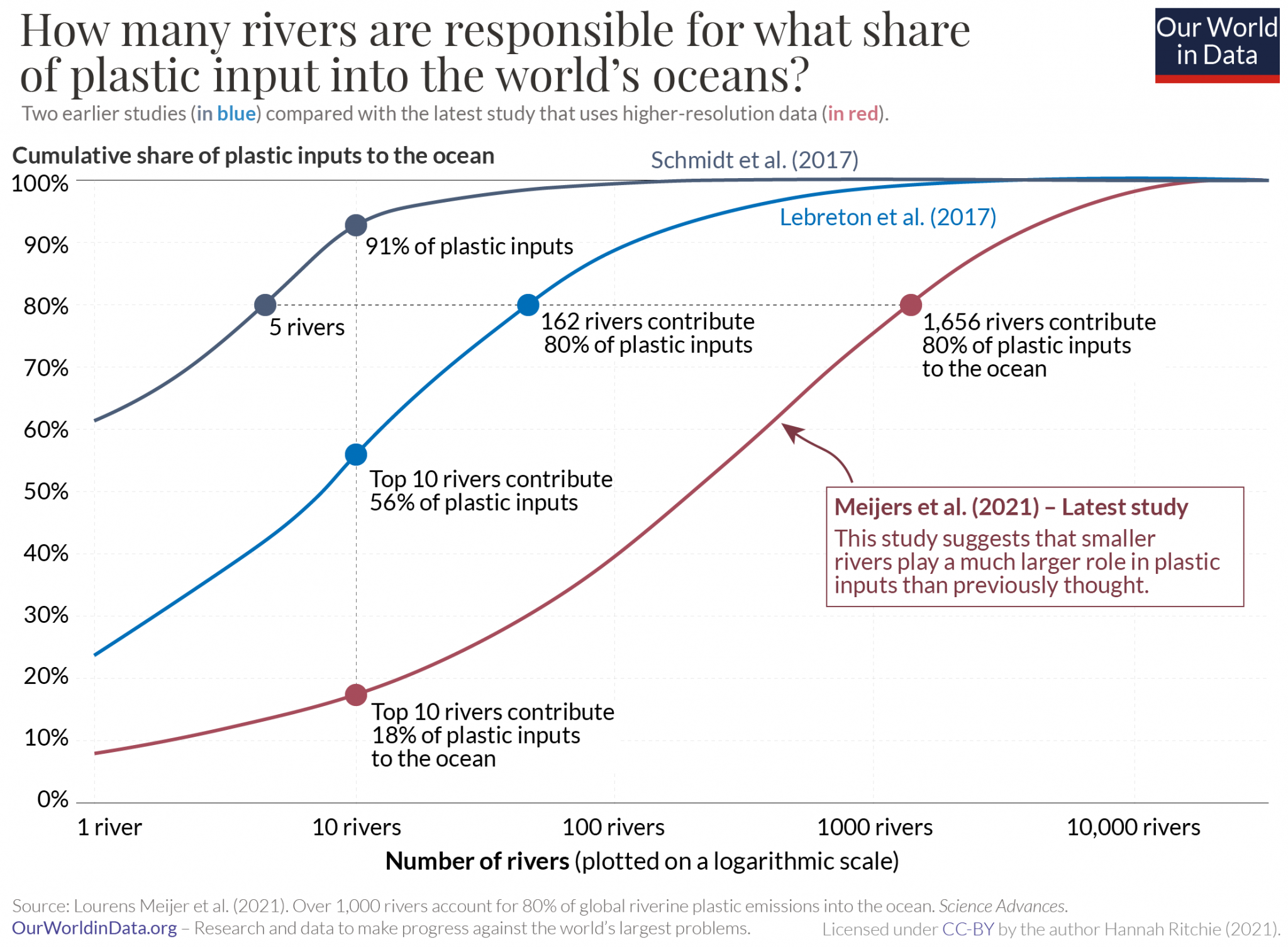

But more importantly, the latest research suggests that smaller rivers play a much bigger role than previously thought. In the graph, we see the comparison of the last investigation (in red) with the two previous studies that mapped global river flows. This graph shows how many of the rivers with the highest emissions (on the x-axis) make up a certain percentage of plastic inputs (y-axis). Note that the number of rivers on the x-axis is given on a logarithmic scale.

We see the latest research suggesting that the top ten most emitting rivers contribute far less than previously thought - just 18% of plastics compared to 56% and 91% in previous studies. And to represent 80% of the plastics in rivers, we must include the 1,656 main rivers. This compares with previous studies that suggested that the five or 162 largest rivers were responsible for 80%.

This makes a big difference in the way we approach plastic pollution. If five rivers were responsible for most of the problem, then we should concentrate most of our efforts there. A targeted approach. But if this encompasses thousands of rivers, we will need to launch a much broader network of mitigation efforts.

Why are the latest results so different? Previous studies were based on simpler models of waste generation in the world's watersheds. They made evaluations of the amount of mismanaged waste generated in each basin; population density in the area; and correlative models of plastic concentrations in surface rivers. They then used these relationships to model the amount of pollution in watersheds where no recorded data on river plastics was available. This meant that the largest emitters were believed to be very large river basins hosting large populations and poor waste management practices. The Yangtze, Xi, and Huangpu rivers in China; the Ganges in India; the Cross in Nigeria; and the Amazon in Brazil were the great rivers that topped the list.

The latest analysis builds on this earlier research with much higher resolution data. Models the deterministic drivers of how plastic is transported using wind and precipitation patterns and river discharge data, as well as factors that affect the likelihood of plastic entering rivers first and then the ocean, such as proximity of populations to the river; distance to the ocean; the slope of the land and the types of land use. These higher resolution data were based on several years of research and calibrations of these models in 66 rivers in 14 countries.

These higher resolution data show that these factors that affect the likelihood of plastics not only reaching the river but also reaching the ocean play a much larger role than the size of the river basin itself. This means that many smaller rivers play a bigger role than we thought.

Which rivers emit the most plastic into the ocean?

To tackle plastic pollution, we need to know which rivers these plastics come from. It also helps if we understand why these rivers emit so much.

Most of the world's largest emitting rivers are in Asia, with some also in East Africa and the Caribbean. In the graph, we see the ten largest contributors. This is shown as the share of each river in the world total.

Seven of the top ten rivers are in the Philippines. Two are in India and one in Malaysia. The Pasig River in the Philippines alone accounts for 6.4% of global river plastics. This paints a very different picture from previous studies in which Asia's largest rivers, the Yangtze, Xi, and Huangpu rivers in China and the Ganges in India, were dominant.

What are the characteristics of the largest emitting rivers?

First, plastic pollution is dominant where local waste management practices are poor. This means that there is a large amount of poorly managed plastic waste that can enter rivers and the ocean in the first place. This makes it clear that improving waste management is essential if we want to tackle plastic pollution. Second, the largest emitters tend to have nearby cities: this means that there are many paved surfaces where both water and plastic can drain into river outlets. Cities like Jakarta in Indonesia and Manila in the Philippines are drained by relatively small rivers, but they account for a large part of plastic emissions. Third, river basins had high rates of precipitation (meaning that the plastics were washed into the rivers and the flow rate from the rivers to the ocean was high). Fourth, distance matters: the largest emitting rivers had nearby cities and were also very close to the coast.

The study authors illustrate the importance of additional climate, watershed terrain, and proximity factors with a real-life example. The Ciliwung River Basin in Java is 275 times smaller than the Rhine River Basin in Europe and generates 75% less plastic waste. However, it emits 100 times more plastic into the ocean each year (200 to 300 tons versus just 3 to 5 tons). The Ciliwung River emits much more plastic into the ocean, despite being much smaller because waste from the basin is generated very close to the river (which means that the plastic enters the river network first) and the river network as well. it is much closer to the river. Ocean. It also rains much more, which means that plastic waste is transported more easily than in the Rhine basin.

Credits: Main photo by Marta Ortigosa

0 Comments